Informations sur l’INHA, ses actualités, les domaines et projets de recherche, l’offre de services et les publications de l’INHA.

Perspective : actualité en histoire de l’art, no. 2027 – 1 : Figures of naturalism

Call for contributions

| Updated on 21 November 2025

Ongoing

Deadline January 12th, 2026

In line with its editorial policy focused on the history of the discipline, Perspective has chosen to devote its next issue to naturalism, a complex question which goes beyond the framework of art history in various respects and one which its practitioners have approached in multiple ways. The theme is eminently topical, given its resonance with the ecological issues that are now at the forefront of political debates, as well as research in the natural and social sciences and the humanities. Naturalism is thus one of the concepts at the intersection of art history, other scholarly disciplines and social issues that Perspective seeks to highlight. The objective of this issue is to trace the use of naturalism in the history of art and explore the changes in the concept that have most marked the discipline in recent years by examining the most varied time periods and cultural areas possible.

Context

The term “figures”, in the geometrical and metaphorical sense of forms, singular historical and cultural configurations, calls for identifying, investigating and understanding the different definitions of naturalism that the history of art has produced, depending on their specific intellectual contexts. We are therefore particularly interested in proposals based on a reflexive historiographic, theoretical or methodological approach to the concept.

1. The naturalist school: a 19th-century artistic movement

First of all, we are interested in the naturalist school of painting as it was defined in the second half of the 19th century (Castagnary, [1857-1870] 1892); David-Sauvageot, 1889; Thomson, 2021) with regard to painters such as Gustave Courbet and Théodore Rousseau, who sought truth in nature, relied on modern rationalism and strove for a more just representation of society. The term thus took on a political and moral connotation in that those supporting the school often shared socialist ideas and those who opposed it (cf. the criticisms waged against Émile Zola, the leading figure of the naturalists in literature) reproached its indulgence for crude images of the dregs of society. The questions raised here might include the discourse promoting this artistic movement (how it differs, for example, from realism), its justifications (what “nature” are we speaking about?) and its theoretical and historical extent (for Jules-Antoine Castagnary, naturalism went back to Cimabue); its possible origins in the artistic literature (e.g., Giovan Pietro Bellori’s disdainful qualification of Caravaggio’s followers as “naturalisti” in L’Idea del pittore, dello scultore e dell’architetto [1664]; see his Vite de’ pittori, scultori et architetti moderni, ed. E. Borea, Turin, 1976: 21-22), or rather, in the natural sciences (since the 18th century, “naturalists” have primarily designated scholars studying nature).

2. Naturalist arts and sciences of the past

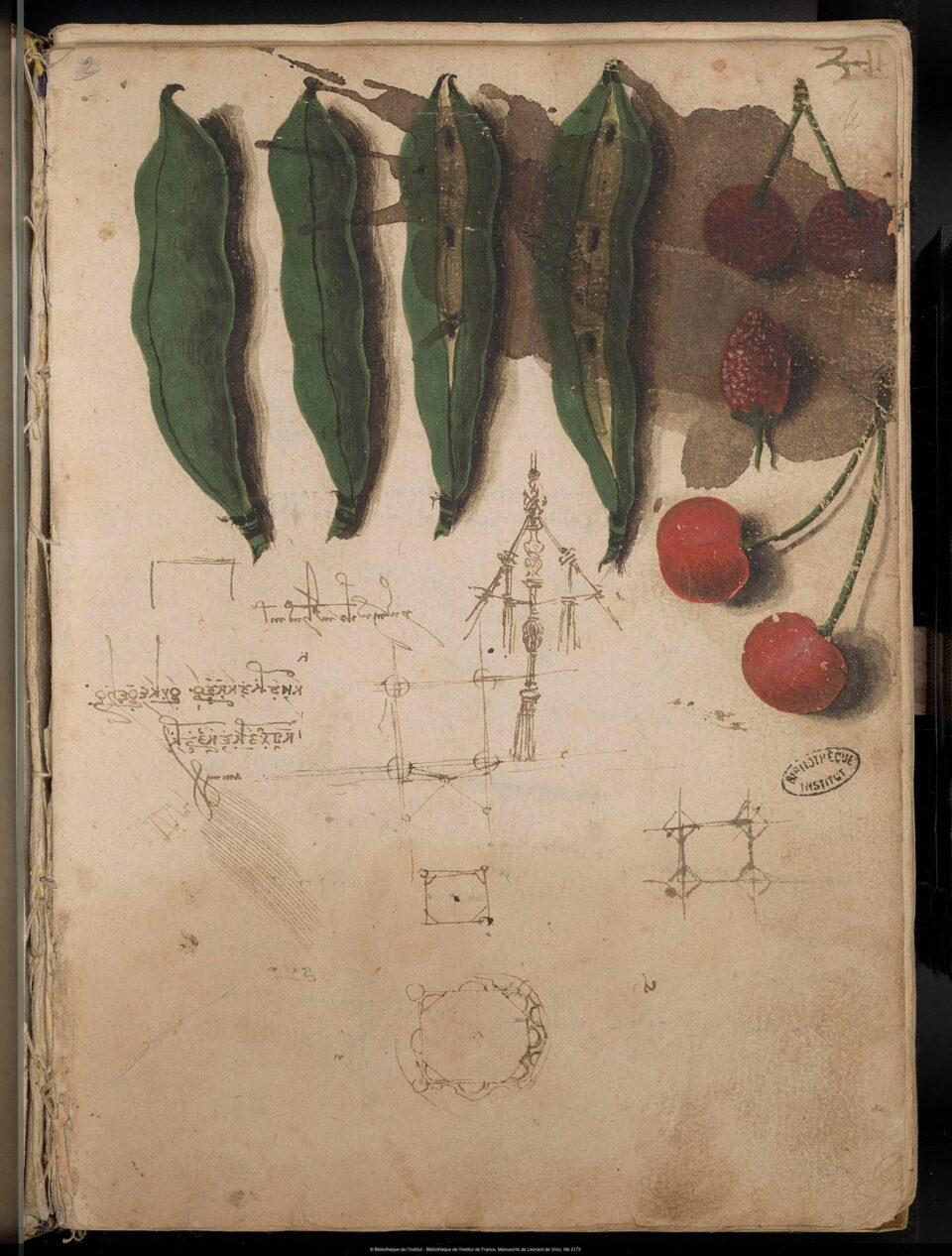

A second research area concerns naturalist representations aimed at studying and promoting nature as a physical reality. In its first complete edition (1694), the dictionary of the Académie Française defined a “naturalist” as a person who, like Aristotle, was devoted to the study of nature. In this sense, naturalist artists and scholars would be observers of plant and animal life, rock formations, oceans and stars, bacteria and insects, who employ their knowledge to represent the visible. While this field has been well explored since the pioneering studies of Erwin Panofsky on Galileo (Panofsky, 1954) or Ernst Kris on the rustic style (Kris, [1926] 2023), it has undergone many changes and has been considerably developed in recent years (Felfe, Sass, 2019). Studies on naturalist artists have helped to extend the boundaries of the discipline by considering topics that had long been ignored by art historians, such as late medieval marginal illustrations (Tongiorgi Tomasi, 1984), the arts of 16th-century gardens (Battisti, 1972; Brunon, 2001), scientific illustration from the 16th to the 18th century (Ackerman, 1985; O’Malley, Meyers, 2008) and taxidermy or fishkeeping in the 19th century (Laugée, 2022; Le Gall, 2022). Wildlife art, which was not highly regarded in the past, is now enjoying renewed interest among researchers who compare this production to knowledge about domestic and wild animals during the same period. The question here is how such studies challenge art history’s conventional hierarchies and enrich the discipline.

3. Naturalism as a fundamental principle of art

Third, naturalism seems to have become a widely used principle in art history during the first half of the 20th century, no longer to designate a specific school of painting but as one of the fundamental principles of artistic expression. Certain authors thus pointed to naturalist trends in medieval art (Dvořák, 1919; White, 1947) or ancient art, and describing an artwork as naturalist had almost become a compliment, as well as a sign of modernity. According to David Summers, this radical approach to visual naturalism was based on a presumed correspondence between the elements of the art in question and those of optical experience (Summers, 1987: 3). Briefly stated, in 1920, any work that appeared to be an imitation of reality could be described as naturalist. For the purposes of the present issue, we would be interested in a review of the debates that opposed the major art historians of that period concerning the origins of naturalism and its underlying rationales: can we speak of progress in the arts according to their degree of naturalism? Does the desire to imitate nature mean seeking to function in the same way, to know it, master it, or discover its aesthetic qualities? Is the source of artistic naturalism to be sought in universal human psychology or the material living conditions of certain societies? Has the discovery of prehistoric art overturned the convictions of art historians about the origins of the imitation of nature? What were the criticisms provoked by this extended use of naturalism, which justified its replacement or abandon? How is it treated today (Kemp, 1990; Campbell, 2010; Barbottin, 2013; Guérin, Sapir, 2016; Boto Varela, Serrano Coll, McNeill, 2020)? Another issue at stake here is the distinction between mimetic practices that exist in several cultures and at different time periods and the naturalist spirit, in the sense of an undertaking aimed at the study of nature.

4. At the intersection of art history, the natural and social sciences and the humanities: the new naturalisms

It is also important to examine contemporary approaches to naturalism, in art history, the humanities and the natural sciences alike. In the history of science, philosophy and anthropology, naturalism has become a subject of investigation in its own right. How do art historians receive, utilise and/or criticise these studies? We can cite in particular science historians Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison, whose Objectivity (Daston, Galison, 2007) challenges the historical model prevailing, for example, in the work of Ernst Gombrich (Gombrich, 1960): rather than placing the representation of nature within a linear continuum (“progress”) common to art and science, between the 15th and 19th centuries, they posit a more discontinuous evolution of the regimes of truth, ways of observing and naturalistic images. Another relevant approach is that of anthropologist Philippe Descola who, in Les Formes du visible (Descola, 2021), considers naturalism as an ontology, a way of dividing up the world intellectually. For Descola, it is typical of modern western culture and an intrinsic part of European and North American colonialism and extractivism since the 16th century, as symbolised by the form of the modern portrait and landscape. He thus seems to agree with Gombrich, whose ideas on the subject have been admirably summed up in a single phrase by James Elkins: “Naturalism is, in short, the history of western art” (James Elkins, Stories of Art, New York/London, Routledge, 2002: 60). But where Gombrich perhaps sees a mark of western superiority, Descola finds a problem, which echoes certain political positions today.

On this point, we are particularly open to ecocritical and ecofeminist approaches to art, in order to explore the ways history draws on them and reconsider the history of the landscape, especially in terms of the concept of the Anthropocene (Arnold, 1998; Thomas, 2000; Nisbet, 2014; Demos, 2016; Patrizio, 2018; Ramade, 2022; Bessette, 2024; Fowkes, Fowkes, 2025), or to examine the museum and the ecological interventions transforming it (Domínguez Rubio, 2020; Quenet, 2024). Alongside Descola’s anthropology of nature, we have seen the emergence of artistic, visual and social narratives about human-animal relationships or the climate within the fields of animal studies or climatology (Rader, Cain, 2014; Cronin, 2018). Studies on colonialism and racism also provide a useful point of view for understanding cultural, visual and artistic phenomena such as tropicalism or primitivism (Noël, 2021). Last of all, we can note the recent spread of an art history investigating the origins of the materials used by artists or a history of decorative arts that seeks to bring out not only the aesthetic aspects of ornaments but their the economic and colonial implications. In all these areas, we would like to evaluate the contributions of the social history of animal representations and the environmental history of art as a way of studying the impact of human activity on the planet, its landscapes and its climate.

At the other end of the spectrum, however, certain specialists reject this ontological version of naturalism and its negative political implications and opt to study naturalist arts that manifest a detailed, sensitive attention to the environment (Zhong Mengual, 2021). Some of them thus maintain that a truly ecological history of the landscape should be free of all references to humans (Gaynor, McLean, 2005; Schlesser, 2016). Others, countering the idea that naturalism reflects a strictly modern, western way of thinking, apply it to prehistoric art (Moro Abadía, González Morales, Palacio Pérez, 2012; Guy, 2017), medieval art or non-western societies (Duran, 2001). In sum, we are seeking to address the contemporary debate on naturalism as a way of seeing and representing the world from the standpoint of art history.

5. A Natural History of Art

The question of naturalism also leads us to consider what today’s natural sciences can contribute to the knowledge of art and its history. How do the neurosciences or behavioural psychology, for example, attempt to naturalise aesthetic responses, artistic creativity or the act of imitation (Dissanayake, 1995; Onians, 2007)? What are the bases of a natural history of art (Onians, 1996; Prévost, 2025) that places the appearance of forms in nature and art on the same level and studies the animal origins of culture (Lestel, 2001; Harkett, Hornstein, 2025)?

6. Major Figures

A final approach entails the historiography of the prominent personalities – art critics, artists, art historians, philosophers of art, scientists coming from other disciplines – who have helped to make the concept of naturalism exist in art history. Here, intellectual biographies will allow us to study works of authors who have provided outstanding, original, noteworthy definitions of naturalism – on the one hand, individuals classified as “naturalists” (scientists who study nature), those who develop a theory or practice of art or a naturalist perspective on art, and, on the other, individuals (artists, specialists in the field of art) who identify a naturalist art. By way of example, we can cite well-known figures such as Galileo (the subject of classic studies by Panofsky [Panofsky, 1954], David Freedberg [Freedberg, 2002] and Horst Bredekamp [Bredekamp, 2007]), Charles Darwin, whose importance for the art of his time has been recognised in several recent exhibitions [Donald, Munro, 2009; Bossi, 2020]), art critic Castagnary (said to be the inventor of the “naturalist movement” in painting as of 1863 [Castagnary, (1857-1870) 1892]), Wilhelm Worringer (who considered it to be one of the two great universal trends in art, alongside that of stylisation [Worringer, (1907) 1953]). While their fascinating writings clearly deserve to be re-examined in the light of the vast bibliography now devoted to them, this issue of Perspective is also intended to draw attention to lesser-known or less prominent figures, whose unexplored contributions can allow us to reconsider the construction of naturalism as an art-historical category and reevaluate its impact.

Topics

In summary, the basic themes which should be addressed by proposed contributions to this issue of Perspective, are the following:

- The naturalist school: the historiography of a 19th-century painting movement, its protagonists, discourse, controversies, extended spheres, limits.

- Naturalist arts and sciences of the past: scientific illustration, taxidermy, animal and wildlife art.

- Naturalism as a fundamental principle in art: art-historical debates in the first half of the 20th century on the imitation of nature, its origins and relationships with the history of mentalities, psychology, the evolution of civilisations. Critical views of its contemporary uses.

- The new naturalisms: the comparative history of the natural sciences and scientific imagery; the anthropology of nature, naturalism as a western ontology and its modes of representation; animal studies and the social representation of animals; the environmental history of art and the anthropization of the planet; ecocritical approaches to art; sensitive naturalism.

- A natural history of art: art and neurosciences, the naturalisation of creativity and aesthetic judgement; the animal origins of culture; animal-made arts.

- Major figures: intellectual biographies of individuals marking the history and theory of relationships between art and naturalism.

[translation: Miriam Rosen]

The journal Perspective : actualité en histoire de l’art

Published by the Institut national d’histoire de l’art (INHA) since 2006, Perspective is a biannual journal which aims to bring out the diversity of current research in art history, highly situated and explicitly aware of its own historicity. It bears witness to the historiographic debates within the field without forgetting to engage with images and works of art themselves, updating their interpretations as well as fostering intra- and inter-disciplinary reflection between art history and other fields of research, the humanities in particular. In so doing, it also puts into action the “law of the good neighbor” as conceived by Aby Warburg. All geographical areas, periods, and media are welcome.

The journal publishes scholarly texts which offer innovative perspectives on a given theme. Its authors contextualize their arguments; using case studies allows them to interrogate the discipline, its methods, its history, and its limits. Moreover, articles that are proposed to the editorial committee should necessarily include a methodological dimension, provide an epistemological contribution, or offer a significant and original historiographic evaluation. Depending on the subject, the wider bibliographical corpus and the geographical area and time period under consideration, two types of contributions are possible:

- Focus: an article based on a specific case that permits the examination of a historiographic, theoretical or methodological question of current interest (3,500-4,000 words / 20,000-25,000 characters);

- Wide Angle: an essay or critical assessment addressing a broader question, an art-historical movement or a methodological or theoretical issue that takes into account recent changes in orientation or approaches on the basis of a selective bibliography (7,000 words / 40,000-45,000 characters, excluding the bibliography).

How to Apply

Figures of naturalism, no. 2027 – 1

Editor: Thomas Golsenne (INHA)

Editorial board/Comité de rédaction here.

Please send your proposals (a summary of 200-500 words/ 2,000-3,000 characters, a working title, a short bibliography on the subject and a brief biography) to the editors (revue-perspective@inha.fr). Proposal deadline: 12 January 2026.

Proposals will be examined by the editorial board regardless of language (the translation of articles accepted for publication is handled by Perspective).

The authors of the pre-selected projects will be informed of the editorial board’s decision in February 2026. The full articles must be received by 1st June 2026. The texts submitted (4,000-7,000 words/25,000-45,000 characters, depending on the format chosen) will be accepted in final form after an anonymous peer-review process.